Featured Artist: Mark Brennan

28 Nov 2024

Throughout human history, nature has been a profound source of artistic inspiration. In this series, we talk with artists whose work is inspired by, created in, or connected to the brilliant nature in the Nature Trust’s care.

Mark Brennan at the opening of his recent exhibition, Kissing the Shoreline, with Nature Trust staff Christina and Riki.

Mark Brennan is a Canadian artist whose work is an exploration of the human connection and contemporary use of the landscape. He works primarily as a landscape painter and photographer.

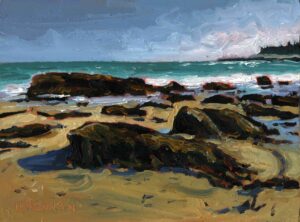

His most recent work, Kissing the Shoreline, exhibited publicly in November 2024 at Argyle Fine Art in Halifax, Nova Scotia. This work is a testament to the remaining coastal wilderness of Nova Scotia but also a voice calling out for its protection as the marine environment experiences significant change through human encroachment and climate change.

“During my kayaking trips I have experienced breathtaking natural moments in nature that have given me pause to consider the incredible intrinsic value of the marine ecosystems, meaning that what I come to understand is that these places have a value unto themselves, they are important because they are simply there. Much work has been undertaken to limit species loss in Nova Scotia through a growing network of land based protected areas and I feel that the frontier of this work lies now in protection of coastal areas. My work here looks to express both depth of experience and also the fragility of the marine environment as I understand it.”

What inspired you to create your latest series of painted artworks, entitled Kissing the Shoreline?

I grew up in Scotland on the West Coast, on the edge of the Scottish Highlands, and formed a bond in childhood with the idea of wilderness. This love of landscape and of nature was a catalyst that pushed me into becoming a painter, I was trying to express the bond I had felt while in the natural world as a child.

Over my career, I have painted mainly inland wilderness areas across Canada, and it seemed to be a natural progression to venture more towards the coastlines. Before the Covid pandemic I had produced a body of work in black-and-white film, where I explored the Nova Scotia coast, it took 2 years.

This new work, Kissing The Shoreline, seems to be an extension of the earlier photographs but there is a message being portrayed and that is the Nova Scotia coastline holds something extremely special, extremely delicate, and is worthy of our attention in a way that does not undermine the natural processes of these ecosystems.

I think all of us realize that in the near future there will be wind farms off of the coast of our province and other industrial projects, and as I’m sure we have all noticed humans love to live near the sea. There has been an expansion of the population more and more into remote coastal areas. When this happens, there is increasing pressure on coastal ecosystems to provide intrusive recreational opportunities that can severely impact these places. We had an example of this with Owls Head.

This body of work is a contemporary snapshot of some of our coast before much of this change is going to take place. It is bound to happen, and I wanted my work to stand as a record of what was but also to draw attention to those who make decisions that there is something very special here that does not have a voice in the human world. My work seems to be a small voice for these species.

Your paintings feel deeply connected to the solitude of remote wilderness; personal yet bold. Do you go out into nature with the intention of capturing it in a certain style, or is there something about the way you experience these remote locations that influences your choice of colour and texture?

My style as an artist is one that has evolved over the past 35 years. When I first arrived in Canada in 1989, I worked as a framer in an art gallery and was exposed to Canadian art for the first time. The gallery owner, Jean Stewart, was also an artist, she took lessons from painters who could trace their lineage back to the Group Of Seven. When I first saw an exhibition of the group in Toronto at the AGO during a train trip across Canada, I was brought to tears. These painters had expressed perfectly what I had felt all my life.

Wave, Taylor Head, Nova Scotia. Oil on panel, 6×8 inches. By Mark Brennan (2023).

There is no doubt that these artists have influenced my style – I would say though that being in a remote location such as the NS coastlines I have explored over the past three years, I do feel a tangible, physical effect on my body of calm, but also there is an excitement and vigour when I see, hear, touch and smell these places.

I use all techniques to portray the landscape, from the lightest of touches to bold long brushstrokes that evoke form and pattern. I try not to have an idea of the outcome of the work in my mind, but let it flow naturally to the point where I am close. I am always striving for something spontaneous that contains a sense of freedom. I feel.

Always in the back of my mind, though is that while I am portraying the landscape through paint I want to make this work something that can exist on its own, as a thing that is created through first hand experience, but in a way is separate from the landscape, although it is still an expression of it. From it, not ‘of’ the landscape.

I have this sense that being in the natural world is where we are supposed to be, so many of us are drawn to nature as a way of healing and recovering from busy lives.

Much of my life has been an immersion into nature and through this I have come to understand some of the intangible subtleties of nature. This is something that I find fascinating. At times I have found myself resting in the woods watching the play of light over leaves or listening to the faintest sounds like the hooves of a deer as it runs off or the distant call of a raven that in comes with the wind. All of these things I try to bring to a focus point of energy to bring them into my work.

Can you describe your process of creating a painted landscape, from how you select a particular location, through to creating your larger works? How do you hold onto the experience of being outdoors in a wild location, when working later on, indoors?

To produce a finished painting, I have to have been in the landscape from which it came. The areas I go to have to contain all the attributes within the land that generate and trigger ideas. One of the most special places for this I have ever been to is the Tobeatic wilderness in Nova Scotia. The landscape here tends to have a randomness about it. There is a great deal of remnant glacial boulders lying in bodies of water. Bogs with old snags with the backdrop of hills and deep forest, all these things combine to give ideas. I call these places the sweet spots. They are parts of the landscape that evokes the very essence of place. So my work usually starts with noticing or seeing something that points to a possibility. Or it could be something as simple as the vibrancy of a sunrise where I will use the colour and forms of the sky along anything else I encounter to pull together a finished painting. I will rearrange rocks and other forms, as I need to on the panel or canvas.

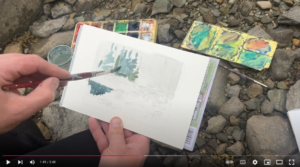

A moment from Mark Brennan’s film, “Sketching 100 Wild Islands, Nova Scotia.” Click the image to watch the 4-minute film.

Sometimes I like to produce a gouche sketch on location or put down the basic composition with notes on colour in pencil. When I’m moving quickly through a landscape I will photo sketch using either my smart phone or camera and refer to this later mostly for compositional reference.

If I haven’t painted on location I will usually work up a small oil sketch in the studio either immediately or a day or two after returning from an excursion. These oil sketches add up and in the last series I did on the coastal landscapes of Nova Scotia there were 31 small 6 x 8“ sketches produced.

Over a period of time I will look at these sketches and begin dividing them up into works that may or may not have the attributes to paint something larger. This is a slow process of whittling down to the point where I eventually will have a few pieces that call out to be painted larger.

The process of working a small sketch into a large piece is all about maintaining the initial interaction with the landscape. This for me is perhaps the most difficult part of creating a painting. I pull on the entire experience and when the time is right, I will attack a blank panel or canvas with everything I have, painting with awareness and depth of knowledge while trying to maintain what I first encountered. This is exhausting and I find I am unable to paint for 2 to 3 weeks afterwards because of the mental effort required. To maintain that spontaneous reaction to the land I attempt to paint also from my subconscious where I am reacting to each stroke as the painting progresses. Often, after finishing a painting I cannot remember much about the actual process and sometimes I look at my own work afterwards and wonder how I managed to paint it!

With all my work, I usually leave them alone after the first attempt at painting a piece. Once the memory of the work has subsided, I will re-return to the painting to see it with fresh eyes, and from here I can make adjustments without having a preconceived idea of what I was trying to capture. This keeps the work fresh and unlabored.

You also create photographic landscapes of Nova Scotia, which feel just as compelling and emotional as your painted works. How do you choose which medium you will use to express your connection to a landscape?

When I served in the Royal Navy, part of that time was as a ships photographer. My tasks involved, capturing the crew in portraits or visits by officials and other work that involved subjects that were more to do with operational tasks. This was during the Cold War. I was very young at that time, 17 or 18 years old and photography was how I first began to express myself. As time passed the ship would spend a lot of time up in the Arctic and to pass the days I purchased a small watercolour set and began to teach myself how to paint. So I am well-versed in both mediums and have an equal passion for both.

Cape Breton Highland. By Mark Brennan.

My work as a photographer these days is mostly in film, using medium format, and to me it has a similar process as painting. I enjoy making a photograph the same way I enjoy making a painting. The photographic work tends to be more attributed to working to produce a body of work about a particular subject or from a particular landscape. So there is more structure in this medium for me. I’m trying to not produce individual photographs, but work that can come together to form a series.

In the spring of 2024 I visited the same place from the end of February until the first week of June photographing at least twice a week the emerging spring. This is part of a group effort with other artists in the USA and UK. I plan to do this again in the spring of 2025. It would be very tough to capture and paint a body of work like this in paintings. So in this case, the camera is the chosen medium.

Each one of the mediums is a tool for expression, but in painting, I am able to invent much more than I could in photography, although with the photograph, we have the ability to see a place over a period of time or through the seasons, which is enthralling. Photography can capture a Time-lapse of the land, it allows us to experience a place in ways we would never have seen otherwise, especially if we are producing a body of work from one area. Humans tend to see the landscape in short periods of time, and along with that our memories are also short. For instance if I made a photograph of the same tree every week for a year a deeper understanding would come to us of the patterns and processes within the landscape that we do not see or experience. So I choose my medium based on the outcome I want.

At least one of the works in Kissing the Shoreline portrays land protected by the Nature Trust – can you talk about the connection between conservation (or protected land), and your artwork?

I had mentioned in an earlier question that I had formed a deep bond with nature at a very young age. There is a sense of wholeness in nature and as I grew older, I came to seek it out as a way to add a richness to my life.

East Village Beach, Sand Cove, Seal Island. Oil, 6×8. By Mark Brennan (2023).

This connection is compelling and pushes the artist whether they are painters, poets, musicians, or writers to express something that is profound and has changed them. So for me, nature compels or asks me and many others to tell its story.

Nature has also taught me to be compassionate and have empathy for other species, all of which do not have a voice in the human world. From a love of something comes action, it is why people support the work of organizations like the Nature Trust. On an emotional level my work is no different than someone donating a piece of land for its preservation.

In the 1990s, I spent time working to push through the first protected areas in Nova Scotia. Obviously this was a labour of love but to conjure an image of a future where there might not be any protected land is something that does not sit with me very well. For anyone who loves nature, this is not the world we want to see.

The human changed landscape does not hold the richness and diversity of life and nor does it allow the natural processes to occur as they have since the last ice age and beyond.

I would like those who look at my work to have some kind of a response where it renders something positive within them, something that compels them to pay attention to the landscapes and watersheds they live within and maybe even to develop or deepen their relationships with nature no matter if they live in a city or a rural area. These small seeds that all of us involved in conservation can plant in others can have the ability to become a greater voice for change in a world that desperately needs it.

Has your work as a Property Guardian for the Nature Trust changed the way you view nature, or influenced your artwork in any way?

Being a Property Guardian fulfils a need in me to do good work. Knowing that I am making a contribution pushes back the negativity we can feel about the state of the world today. I get a similar kind of gratification when I paint as I do when I’m walking the land of the Nature Trust.

The Nature Trust work has also coaxed me into meeting like-minded individuals who have similar values. This gives me hope. Hope seems to be the defining value of our time and I find myself searching for it everywhere, and finding it.

All of us have the chance to make a contribution that betters the lives of people and places and I think, if we can, we all have a responsibility to work for positive change. There is joy in doing!

Can you tell us a bit about your next artistic endeavour?

My next artistic endeavour is still being conjured from the depths of a busy mind! I like to spend a lot of time thinking about new work, it is a sort of rendering process where I allow myself to be patient and wait for ideas to come. The ideas usually stem from reading or seeing something that catches my attention or even a conversation with someone.

I will take these ideas and work with them through thinking. If there is a possibility of something being started, then I will make an attempt usually by going to a particular place to see if it has any value with regards to the possibly of making a body of work. I might even take a few photographs or paint some pieces from a location. Sometimes I am pulled back to revisit and this might be the start of something fresh.

Right now I’m interested in photographing a particular natural location near me in medium format film. There are two areas, one is a watercourse and the other a piece of land where an old Homestead used to sit. I’m still thinking about each location and the attributes they might have over something very long-term.

Winter is coming, and I know that as the snow returns I will be compelled to push into wild places on snowshoes, the winter is something I love to paint, there is an abstraction to the landscape that can give the work a freshness. I am always drawn to where the open rivers meets the land in midwinter. Those contrasting edges of water, snow, and ice has everything a painter could need.

Finally, I would like to acknowledge that we are in Mi’kma’ki, the traditional territory of the Mi’kmaq people.

We are so grateful to Mark for sharing this insight and conversation with us. To learn more about his art across multiple media, visit his website. You might also enjoy listening to his collection of soundscapes, wild sound recordings of a changing natural world.

If you are an artist and would like to share the story of how nature influences your art, please reach out to us at nature@nsnt.ca!